1985年春天,我第一次訪問中國東海岸的度假勝地北戴河,此後每年都會回來,主要是作為遷徙調查和觀鳥之旅的領隊或聯合領隊,也有幾次是為了度假。總而言之,我在這個小鎮待了一年多,獲得了超過 300 名亞洲移民的北戴河名單,並體驗了絕佳的觀鳥體驗。此外,為了刺激保護工作——部分是在我的敦促下,1990年春天,該鎮建立了一個不起眼的自然保護區。

也就是說,如果沒有景觀美化工作,就不會令人印象深刻。我記得我曾向國際鶴類基金會主任喬治·阿奇博爾德博士大肆談論該保護區的潛力。我說,考慮到北戴河上空飛行路線的鳥類數量,該保護區的鳥類密度可以與北美最好的候鳥陷阱一樣高。 “是的,”阿奇博爾德回答道。 “但這些都是巨型蜱蟲。”

[本文最初發表於 Birding(美國觀鳥協會):1994 年 10 月和 1995 年 2 月。]

北戴河巨蜱和遷徙走廊

東方白鸛等巨型蜱蟲(白鸛),實際上僅限於俄羅斯東部和中國;大約有 3000 名世界人口,其中大部分在秋季遷徙到北戴河。巨型蜱蟲,如遠東特有的三隻瀕臨滅絕的鶴——丹頂鶴 (鶴), 連帽的 (G.莫納查)和白枕(G. vipio)——以及西伯利亞鶴(白鶴芋),在伊朗危在旦夕,但在遠東地區數量接近 3000 艘,經過北戴河時有數百艘。還有桑德斯鷗(黑鷗),世界人口大約為 2000 年,遺鷗(殘遺乳桿菌)(4000-5000),以及諾德曼的青腳鷸(丁香)(1000),這些都為該鎮的小河口增光添彩——僅在北戴河才能經常看到遺鷗遷徙。

此外,還有一些對許多觀鳥者來說具有巨蜱地位的物種,儘管它們在世界範圍內並不稀有和瀕臨滅絕:在英國,我將這種物種稱為“Sibes”。在許多野外指南中,西伯人被列為流浪者,他們總是帶著某種神秘感,因為他們是來自遙遠、難以到達的土地的任性流浪者。即使當它們登陸時,它們似乎也喜歡最遙遠的地方,例如英國的設得蘭群島,以及北美那些被稱為阿圖島和聖勞倫斯島的偏遠岩石塊。

北戴河目前排名 這 看到東亞移民的地方。隨便挑一個到北美的亞洲流浪者,很可能就發生在北戴河。東方 Pratincole (馬爾迪瓦格萊烏拉)?西伯利亞藍知更鳥(藍絲蟲)?西伯利亞紅喉鳥 (E. 卡利奧佩)?眉鶇 (暗鶇)?披針鶯 (披針蝗)?都是常見的。太平洋雨燕(叉尾雨燕; 太平洋鴨)以數千計傳遞。成群的西伯利亞沙鴴造訪河口 (蒙古無魚鱉)。木鷸 (黃胸鷸) 和長腳趾 (小鯽)更喜歡潮濕的稻田,在晚春時節,這裡是尋找白鷚的地方(古斯塔維).

北戴河目前排名 這 看到東亞移民的地方。隨便挑一個到北美的亞洲流浪者,很可能就發生在北戴河。東方 Pratincole (馬爾迪瓦格萊烏拉)?西伯利亞藍知更鳥(藍絲蟲)?西伯利亞紅喉鳥 (E. 卡利奧佩)?眉鶇 (暗鶇)?披針鶯 (披針蝗)?都是常見的。太平洋雨燕(叉尾雨燕; 太平洋鴨)以數千計傳遞。成群的西伯利亞沙鴴造訪河口 (蒙古無魚鱉)。木鷸 (黃胸鷸) 和長腳趾 (小鯽)更喜歡潮濕的稻田,在晚春時節,這裡是尋找白鷚的地方(古斯塔維).

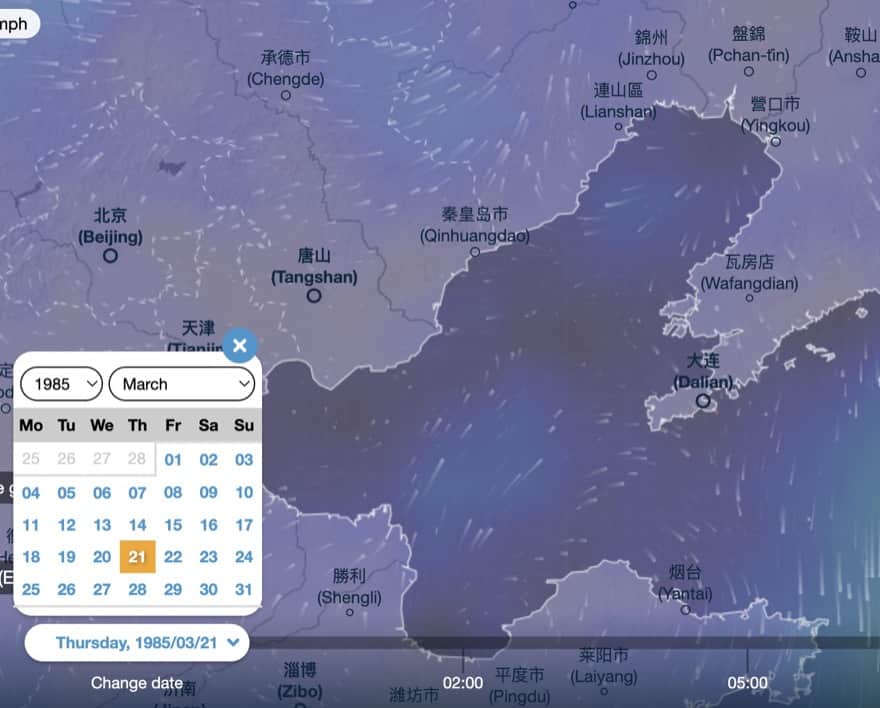

全鎮[洋河北至秦皇島]名錄目前已達390餘種;其中一年內可能會發生 300 多次,全年可能只有 14 次發生——其餘的至少是部分移民。多樣性主要源自於北戴河的位置(地圖)。北戴河位於北京以東280公里處,位於東海最北端的渤海灣邊緣。幾條遷徙路線在該地區交匯,連接中國南部、澳洲、泰國的冬季棲息地,甚至東南非非洲的阿穆爾隼、杜鵑和雨燕,以及從中國東北到俄羅斯北極地區的繁殖地。

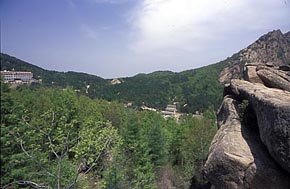

同樣重要的是棲息地的多樣性。儘管自我第一次訪問以來,度假村如雨後春筍般湧現,但河口、樹木繁茂的山丘和溝壑、沿海種植園和兩片淡水沼澤地區仍然存在。所有這些都位於或靠近一個大致呈三角形的岬角,該岬角從原本平坦的海岸線突出,並且本身被侵蝕成較小的岬角——吸引鳴禽和其他在海上遷徙的移民。北戴河三角區主要由花崗岩構成,也形成了低矮(153m)的蓮花山,是觀看可見遷徙的主要有利位置。

飛越該地區的鳥類主要沿著海岸線或海灣和西部山脈之間的狹窄平原飛行。這片平原從北戴河一直延伸到曾經被稱為“滿洲里”的南部地區,顯然是一個遷徙走廊,特別是對於草原和濕地鳥類,如鵝、鴇和鶴來說。

北戴河早春鶴浪

想像一下這個。三月中旬,你到達了北戴河。春天才剛剛開始:潮汐線沿岸有海冰,落葉樹光禿禿的,草因乾冷而泛黃。距離丹麥科學家阿克塞爾·海明森上次對該鎮進行移民調查已有四十年了。你已經閱讀了他的研究結果,這些結果發表在一本不起眼的斯堪的納維亞期刊上的兩篇非常詳細的論文中,並表明你開始的春季調查將產生一些壯觀的觀鳥活動。然而,這四十年裡發生了很多變化——中國人口增加了一倍多,環境惡化,濕地干涸,森林砍伐,狩獵壓力大幅增加。你在北京見到的國家鳥類環誌中心主任告訴你,“北戴河沒有鳥。”

這就是我們1985年調查隊先遣隊的四人所面臨的情況。我們按照喬治·阿奇博爾德的建議於早春抵達,他鼓勵我們留意西伯利亞鶴和其他鶴,它們是遷徙的先鋒。第一天,我們早到似乎很值得——我們看到了 47 個 Common 鶴 和 13 只丹頂鶴,以及西伯利亞口音鳥等越冬鳴禽 夏枯草,以及新抵達的歐亞戴勝 烏普帕埃波普斯 和達烏爾紅尾鴝 金尾鳳凰.

這就是我們1985年調查隊先遣隊的四人所面臨的情況。我們按照喬治·阿奇博爾德的建議於早春抵達,他鼓勵我們留意西伯利亞鶴和其他鶴,它們是遷徙的先鋒。第一天,我們早到似乎很值得——我們看到了 47 個 Common 鶴 和 13 只丹頂鶴,以及西伯利亞口音鳥等越冬鳴禽 夏枯草,以及新抵達的歐亞戴勝 烏普帕埃波普斯 和達烏爾紅尾鴝 金尾鳳凰.

然後,我們開始疑惑。在蓮花山上,我們看著天空尋找遷徙的候鳥,時間一天天過去,但除了偶爾看到成群的豆雁外,什麼也沒看到。 豆雁 和普通起重機。 “你管這個叫什麼,馬丁? “我稱之為‘無鳥’。”我們的一名隊員在漫長的下午值班期間嘀咕道。天氣看起來不錯,天空常常晴朗,微風徐徐。也許人口已經崩潰,鵝和鶴的大飛行已經成為歷史?

但我們沒有考慮到鶴對天氣的挑剔。可能是因為沿海走廊除了濕地中的石質河口外幾乎沒有什麼,鶴只在天氣適宜的日子才會大量飛越北戴河——這一策略幫助它們在兩地之間至少飛行 200 公里。北戴河以南的廣闊平原及其泥濘的河口,以及北邊滿洲的沼澤。

帶來第一波浪潮的天氣變化並不令人吃驚:天空依然晴朗,微風轉向西南,高壓系統向東移開。然而,這對鳥類的影響是巨大的。

3 月21 日,我們第一個「浪潮」日的早晨,是豆雁的蹤跡,它們成群結隊地飛過,數量多達400 隻。它們只是一排排的點,它們接近並飛過我們的觀察點,鳴叫著高聲。隨著鵝的數量逐漸減少,鶴開始飛過。從中午開始,他們就搶盡了風頭。

天氣溫和,幾乎沒有襯衫,我們看到一群群鶴向北飛去。就像鵝一樣,它們是遠處的點線;那些在內陸深處的鳥群,即使與我們齊平,也只不過是一條線,當鳥兒隨著它們的領頭者一起起落時,線就會蕩漾開來。其他羊群也靠近了,有些就從頭頂飛過。我們通過望遠鏡觀察它們,然後用雙筒望遠鏡,然後通過長焦鏡頭拍攝鳥類,並對這些景象和聲音感到驚嘆。

較大的鳥群——100隻或更多——由V形圖案組成,隨著鳥兒的飛行,這些V形圖案相互連鎖、不斷變化,天空書寫著不斷變化的圖案。大多數鳥群都是灰色的鳥:鶴。有些是灰色和白色的混合體,就像普通鶴和西伯利亞鶴一起飛翔一樣。其他通常較小的群體是白鶴:苗條、閃閃發光的西伯利亞鶴,它們的翅膀浸有墨水黑色,還有莊嚴的紅冠鶴,有黑色的副翼和黑色的脖子。天空中響起了鶴的叫聲——康芒鶴和丹頂鶴的叫聲,西伯利亞鶴的高亢、近乎機械的叫聲。

鶴的脈動持續了大約三個小時;下午晚些時候很安靜。很可能,我們看到的鳥類在上午中旬熱氣流形成時就離開了我們以南的中轉站,並打算在夜幕降臨之前至少到達南滿洲的沼澤地。

當天共捕獲豆雁 1016 只、不明雁 533 只、普通鶴 631 只、丹頂鶴 128 只、西伯利亞鶴 122 只。隨之而來的是更多的起重機“波浪”,正如海明森所說的那樣。再次,它們與向東溜走的高壓系統同時發生,產生了相當穩定的條件,風大致沿著鳥類飛行的方向,並且幾乎保證了目的地的良好天氣。 (只是白頭鶴的峰值數量不同;陰天有西南風,下午有小雨,有257只向北飛去。)

春季結束時,我們共有 4409 只普通鶴、244 只丹頂鶴、309 隻白頭鶴和 652 只西伯利亞鶴,以及 1785 隻身份不明的鶴,其中大部分是普通鶴。如果你考慮到每年春天在內布拉斯加州普拉特河停泊的大約50 萬隻沙丘,這幾乎算不上什麼驚天動地的事情,但丹頂鶴、冠鶴和西伯利亞鶴總共只能聚集12,000 只—— 652 只西伯利亞鶴約佔40%當時已知的世界人口。

當鶴遷徙結束時,我們創造了一個笑話。比如說,看著一隊西伯利亞人從城鎮上空經過,我們會高興地互相宣布:“北戴河沒有鳥!”

當然,鶴並不是我們在早春看到的唯一鳥類。隨著他們的浪潮來來去去,整體遷徙正在形成。許多冬季遊客在三月的最後兩週離開;我們到達時常見的西伯利亞口音變得稀少,歐亞雲雀成群 阿勞達阿文西斯 田野裡的鳥兒越來越少,普通金眼鳥的數量也越來越少 布斯帕拉·克蘭古拉 在海上。我們看到其他早期遷徙者向北遷徙:成群的北田鳧 瓦內魯斯, 魯克斯 烏鴉 和達烏爾寒鴉 烏鴉 成百上千隻笨重的大鴇奧蒂斯·塔達(Otis tarda)鬆散地成群結隊,一隻巨大的白尾鷹 白鯨。隨著早起鳥類數量的減少,更多的物種加入了遷徙。

4月9日,低雲和薄霧使我們無法從蓮花山觀看。但我們確實看到了遷移的進展。在海灘小屋裡,我們看到鴨子向北海岸飛去:527 Garganey 鴨, 66 鐮狀青色 鐮形鴨, 377 只 斑嘴鴨 斑嘴鴨,和10只鴛鴦 艾克斯。木鴛鴦的近親 艾克斯·斯彭薩在英國,普通話作為野鳥而被我們所熟悉;但現在我們在前往滿洲和俄羅斯東部河流森林的途中看到了它們真正的野生狀態。

中國沿海春天的鳴禽

在觀看過程中,我們注意到鳴禽從海上飛來。中午時分,偶爾會有鴨群出現,我們有機會在下午騎自行車尋找它們,結果發現鴨群大量湧入——這是一種後果。紅腹藍尾鷸 眼鏡猴 很充足;大多數花園和灌木叢中都能聽到它們的鳴叫聲。它們在仍然光禿禿的植被中飛翔,很容易被發現,讓我們可以欣賞到英俊的藍白相間的雄鳥,它們的側面塗有橙色。小帕拉斯葉鶯喜歡灌木叢和樹木,有時盤旋捕捉昆蟲,有時顫抖著發出一陣旋律優美的歌聲。

還有彩旗:晚期鄉村風格 黃鸝, 成群的黃喉 線蟲,他們興奮時會豎起頂峰。一對長尾朱雀 西伯利亞烏拉古斯 徘徊在鷹溝——它們是體型輕盈的雜技鳥,雄性呈淡粉色,有兩條白色翼條。

另一種徘徊的鳥是一隻未成熟的雄性丑角鴨 表演者,在岩石東海岸附近的海上。我三天前就發現了它,這是一個意想不到的、令人興奮的景象——這是北戴河的第一次,也是中國為數不多的記錄之一(北戴河又出現了兩次目擊事件) ,還有一隻一直想要的救生鳥。

不足為奇的是,一些物種在 4 月 9 日首次出現,並很快變得普遍。一對暗鶯 黑毛柳鷸 黑臉鹀在海濱灌木叢中疲憊不堪,平易近人 灰頭鷴 有兩隻暗色鶇拖著腳步在一塊光禿禿的地面上行走。 鶇 在一片現在已被旅館覆蓋的田野裡,晚上,兩隻東方小草在小水庫上空叫賣昆蟲。

春季遷徙在五月中旬左右達到高峰。由於仍有少數早期候鳥有待發現,大量鳥類主要在此時經過,隨著遷徙速度加快,每天都可能產生新物種,兩週的觀鳥可能會產生 200 種鳥類。

這個月的亮點包括一些令人驚嘆的鳴禽。雄性西伯利亞藍知更鳥上面呈電藍色,下面呈純白色;它們喜歡灌木叢,會在地上跳來跳去,並猛烈地搖動尾巴。同樣偷偷摸摸的還有雄性西伯利亞紅喉鳥,它們把所有的羽毛都放在喉嚨裡。

雖然藍知更鳥和紅喉鶲可能只能短暫地瞥見,但黃腰鶲 花斑鰍 是炫耀。下面它們發出黃色的光,就像原鳴鶯一樣 柑橘原蟲;它們上面是黑色的,有白色的翼條和黃色的臀部。稀有的亞洲天堂-捕手 天堂神龜 它們的羽毛並不特別,只是頭部呈黑色,上面呈紅褐色,下面呈淺灰色,但擁有長而飄逸的尾巴,幾乎是身體長度的兩倍。

雖然藍知更鳥和紅喉鶲可能只能短暫地瞥見,但黃腰鶲 花斑鰍 是炫耀。下面它們發出黃色的光,就像原鳴鶯一樣 柑橘原蟲;它們上面是黑色的,有白色的翼條和黃色的臀部。稀有的亞洲天堂-捕手 天堂神龜 它們的羽毛並不特別,只是頭部呈黑色,上面呈紅褐色,下面呈淺灰色,但擁有長而飄逸的尾巴,幾乎是身體長度的兩倍。

雄性西伯利亞鶇沒有這樣的裝飾,甚至沒有任何顏色 西伯利亞獸。它們是板岩色的黑色,有明顯的白色眉毛(你幾乎不會注意到蒼白的通風口);簡單而引人注目的圖案無疑使他們躋身終極“Sibes”之列。

雄性西伯利亞鶇沒有這樣的裝飾,甚至沒有任何顏色 西伯利亞獸。它們是板岩色的黑色,有明顯的白色眉毛(你幾乎不會注意到蒼白的通風口);簡單而引人注目的圖案無疑使他們躋身終極“Sibes”之列。

成群的黃胸鹀 黃鷂 為欄位新增顏色。普通朱雀 紅雀 紅色雄性聚集在樹上,彼此輕快地吹著口哨。

如果所有這些鳥聽起來都不會挑戰您的識別能力,請嘗試看看此時出現的其他一些鳴禽。例如,柳鶯。現在,即使你所知道的唯一“Phyllosc”是北極鶯 北極松,你很清楚會發生什麼事——這個家族的一些成員看起來很像北極鶯,上半身呈綠色,蒼白的眉毛和深色的眼紋,下半身是白色或灰白色的。

識別早期帕拉斯之葉- 鯽魚 和黃眉[[無知]] P. inornatus 無性,後來的東方冠 P. coronatus,白腿 細線對蝦,北極,稀缺的布萊斯葉- 斑葉松 以及——也許是最新的——雙槓綠色 鉛蝽 鶯的特徵是基於諸如翼條(有嗎?;如果有的話,一兩個,寬還是細?),臀部(如果是黃色,智神星的——這很容易),存在冠條紋,第三邊緣,腿部顏色、下顎顏色;甚至耳罩上的斑點數量——當鳥兒忙著穿過樹葉時不容易注意到。叫聲也有幫助:我仍然發現,截然不同的叫聲是自信地區分北極鶯和兩條紋綠鶯以及高位藍尾鶯的最佳方式 磨刀 有助於尋找不顯眼的白腿葉鶯。呼叫對於辨識北戴河的棕色葉毛蟲也有很大幫助:暗色毛毛蟲、拉德毛毛蟲 P.施瓦齊, 還有——更罕見——黃條紋 華山松 鶯。

然後是蘆葦鶯。最大的——東方蘆葦鶯 東方 Acrocephalus (arundinaceus) — 很簡單,它的臉部圖案有助於將其與類似的厚嘴鶯區分開來 蘆葦。但要挑一隻水田鶯 A.(agricola)tangorum (右)或鈍翅鶯 A. concinens 來自黑眉蘆鶯的寄主 A. 雙三頭肌 五月下旬到來的人依賴於微妙的特徵。

然後是蘆葦鶯。最大的——東方蘆葦鶯 東方 Acrocephalus (arundinaceus) — 很簡單,它的臉部圖案有助於將其與類似的厚嘴鶯區分開來 蘆葦。但要挑一隻水田鶯 A.(agricola)tangorum (右)或鈍翅鶯 A. concinens 來自黑眉蘆鶯的寄主 A. 雙三頭肌 五月下旬到來的人依賴於微妙的特徵。

增添樂趣的是蝗蟲(或“蚱蜢”)鶯,我主要在飛行中看到它們:深色、細尾披針鶯(左)、帕拉斯蚱蜢鶯 塞蒂奧拉 尾巴較長,臀部紅棕色。類似的日本沼澤鶯 鯽魚 似乎更不願意被看見。其他棕色潛潛鳥,如斑點布希鶯 胸慢翅魚 和格雷的蚱蜢鶯 片狀乳酸桿菌,有利於樹木繁茂的地區。

使困惑?我想說,去過北戴河之後你就不會了。但也許你會:對於一些東部古北界鶯來說,辨識技術仍在不斷發展。

七里海和歡樂島

北戴河以南有三個河口區:入海通道狹窄的七里海泥質潟湖、灤河河口和大清河河口沙洲泥灘。對於沿海鴴鷸來說,所有這些都比北戴河要好——因為儘管北戴河吸引了種類繁多的鴴鷸(包括淡水專家,迄今為止有52 種),但它的泥灘和沼澤太小,無法容納大量鳥類。相較之下,我們對這三個地區的幾次考察表明,至少大清河和灤河可以躋身國際重要濕地之列。事實上,大清河複合體可能是東亞頂級鴴鷸類鳥類棲息地之一。

1992 年 5 月,在我共同帶領的一次觀鳥之旅中,我們進行了為期兩天的觀鳥之旅,涵蓋了這三個地點。尤其是去大清河之行,有點像一場賭博,因為我唯一一次五月去的地方是前一年,當時月底,泥灘幾乎空無一人。但這場賭博得到了回報,我們看到了一些壯觀的觀鳥——這兩天我們的名單包括 37 種濱鳥。

1992 年 5 月,在我共同帶領的一次觀鳥之旅中,我們進行了為期兩天的觀鳥之旅,涵蓋了這三個地點。尤其是去大清河之行,有點像一場賭博,因為我唯一一次五月去的地方是前一年,當時月底,泥灘幾乎空無一人。但這場賭博得到了回報,我們看到了一些壯觀的觀鳥——這兩天我們的名單包括 37 種濱鳥。

我們從七里海潟湖以西出發,至少有30隻小杓鷸 微小努門紐斯。愛斯基摩杓鷸的近親 北方豬籠草,小杓鷸較為常見,但其分佈僅限於本地。

然後,前往灤河。濱鳥的數量不多,但有八種海鷗,其中包括五種有著漂亮夏季羽毛的桑德斯海鷗、三種意想不到的遺鷗和一隻小海鷗 小鷗 ——這對中國來說可能只是第五個。一片幼樹種植園裡棲息著大量鶯、畫眉和彩鹀——這是即將發生的事情的跡象。 [可悲的是,據報道,灤河的大部分地區已被包括魚塘在內的開發項目所破壞;據報道摧毀了桑德斯海鷗的棲息地。]

第二天,我們搭船來到大清河口的一個小島。我們在穿越過程中經過的泥灘上棲息著大量濱鳥,包括蒙古鴴、大濱鷸 細嘴鷸, 遠東杓鷸 馬達加斯加努門紐斯,以及 14 種瀕臨絕種的亞洲獵犬 半掌沼澤水母;還有黑嘴鷗和 5000 隻普通黑頭鷗 紅鷗。島上稀疏地覆蓋著灌木、低矮的樹木和長長的草叢,到處都是鳴禽——我在每日日誌中記錄的條目中估計有 230 只(西伯利亞)石聊鳥 虎杖, 50 隻棕色伯勞 冠毛拉尼烏斯 和 20 隻暗鶯,以及 6 個品種的 39 隻畫眉鳥,其中包括令人驚嘆的 7 隻白鱗畫眉鳥 道馬獸 在一叢灌木中。

四天后,兩名瑞典人加入了一群住在北戴河的觀鳥者之中,當我們帶著關於稀有物種和大量候鳥的故事回來時,他們立即訪問了同一個島嶼。他們不僅只是觀看鳴禽,還檢查了島上西海岸的泥漿,發現了一個濱鳥棲息地,棲息著大約 3500 隻紅腹濱鷸 坎努特斯 和 1500 個大結,以及至少 100 個亞洲多巫師。在本月稍後的回程中,我也看到了棲息地。結鳥群規模較小,不到 2000 只,但仍然令人印象深刻,潮水上漲時聚集的其他濱鳥包括大約 1000 只斑尾塍鷸 鹿蹄草。前一天,在東邊 10 公里處的一個沙嘴上,我們的團隊發現了數百隻棲息的濱鳥和 3000 隻東部常見燕鷗 長翅燕鷗。

由於該地區面積很大,有許多沙洲和可以棲息的小島嶼,這些數字可能只代表我們訪問期間出現的海鷗、燕鷗和濱鳥數量的一小部分。至於整個春天期間該地區有多少鳥類——至少目前我們只能猜測。

大清河地區面向南,橫跨一個淺海灣,每年都會有大群的泥灘鳥類棲息,也是大型鳴禽的棲息地,大清河地區可能是亞洲距離德克薩斯州上海岸最近的地區。它的主要觀鳥區——島上有大量的鳴鳥和漲潮時的棲息地——有點像玻利瓦爾平原和高島的結合體。 (這個島的名字呢?「Kwaile Dao」——對於那些因成功的訪問而興奮不已的觀鳥者來說,它被翻譯為「快樂島」。[現在看來我幫助發明了這個名字! ——在與當地導遊發生一些誤解之後,他們確實說這個名字叫“快樂刀”,儘管當地人後來說它叫“十玖陀”,這個名字要平淡得多,沒有現成的翻譯。])

[另一個值得一試的濕地是天馬湖-天馬湖,或天馬湖-位於城鎮西部,由山腳下的水庫形成。絕佳的淺邊緣,上面是草地。]

北戴河流動人口減少

5月底,春季遷徙已接近尾聲;觀鳥的人數通常很少。但考慮到影響因素——春季可能包括下雨或下雨的威脅——可能仍然有不錯的數據。 1991 年 6 月 7 日,該鎮最東端的岬角燈塔角 (Lighthouse Point) 棲息著蘆鶯、頂頭鶯和其他鳴禽。

晚春的候鳥包括沼澤鳥類-黃鰍 Ixobrychus sinensis 和史倫克鰍(Schrenck's Bitterns) I. 韻律, 拜永秧雞 小波札納、蘆葦鶯和蝗鶯,它們的旅程時間與它們潛伏的挺水植被的晚期生長相一致。

晚春的候鳥包括沼澤鳥類-黃鰍 Ixobrychus sinensis 和史倫克鰍(Schrenck's Bitterns) I. 韻律, 拜永秧雞 小波札納、蘆葦鶯和蝗鶯,它們的旅程時間與它們潛伏的挺水植被的晚期生長相一致。

五月底和六月初,有可能出現春季最後的大蜱蟲,即鮮為人知、現已瀕臨滅絕的條紋蘆鶯 高頭鰍 (正確的)。

五月底和六月初,有可能出現春季最後的大蜱蟲,即鮮為人知、現已瀕臨滅絕的條紋蘆鶯 高頭鰍 (正確的)。

儘管與任何遷徙觀察點一樣,每年的觀鳥情況都會有所不同,但很少會令人失望。 “當人們聽到我們今年春天所看到的景象時,”去年一位觀鳥者說道,“這會讓他們大吃一驚。”

但無論是否令人興奮,北戴河的移民也有發人深省的一面。有些物種的數量已經下降——在某些情況下急劇下降——我們今天看到的遷徙可能只是本世紀初遷徙的影子。

我寫「可能是」是因為,儘管本世紀初北戴河地區鳥類的資訊相對豐富,但往往很難與最近的觀測結果進行比較。判斷一個物種的數量是否發生了變化,以及如果發生了變化,變化的程度如何,並不容易。儘管存在這個問題,但對於許多移民來說,我不知道有更好的資訊來評估人口變化。北戴河可能是東亞地區研究最深入的遷徙觀察點,研究可以追溯到 1910 年。

第一項研究是由英國領事約翰·DD·拉圖什(John DD La Touche)完成的,他在中國任職期間對鳥類進行了研究,並編寫了一本全面且至今仍然有用的中國東部鳥類手冊,對中國的鳥類學做出了重大貢獻。 1910年至1917年,他透過自己的觀察以及英國鳥類學傢俱樂部遷徙委員會僱用的收藏家的標本和目擊記錄,對附近秦皇島港口的鳥類進行了研究。

遺憾的是,拉圖什在報告結果時很少給出數字,而是使用「豐富」、「常見」或「稀缺」等評論。很難猜測他對這些術語的使用是否與我們的一致。他將如何報告目前水準的移民情況?因為「豐富」和「非常豐富」這兩個詞在他的論文中出現的頻率比我們今天使用的頻率要高得多,拉圖什在使用這些詞時是否過於自由了?

我們的一個調查小組的一名成員認為他是的。我不相信;拉圖什的著作顯示他頭腦冷靜。如果是這樣,那麼有幾個物種的數量已經經歷了急劇而悲慘的下降。事實上,拉圖什寫道,秋季移民「長流」沿著海岸流過:以今天的標準來看,他的描述似乎有些誇張。

我們與海明森的工作進行比較是比較安全的,海明森對他記錄的物種進行了更全面的描述,通常是一些數字,有時是季節性總數。同樣,問題也存在:海明森是一名孤獨的觀察者——儘管他花錢請僕人尋找成群的鶴、鵝和其他鳥類——在日本佔領的限制下工作。棲息地已經發生了變化:今天的北戴河與他所熟悉的小鎮截然不同,這是一個隨著中國經濟繁榮而不斷擴張的度假勝地。

拋開困難不談,將我們的結果與拉圖什和海明森的結果進行比較,描繪出一幅黯淡的景象。儘管數據可能較差,但情況似乎與北美大致相同,移民數量不斷減少,而造成移民數量下降的原因有很多,所有這些都源於人口數量驚人。

正如您所料,棲息地破壞和破壞在原因清單中名列前茅。春季最後的大蜱蟲-條紋葦鶯,在拉圖什時代曾大量出現,但如今已經很少見了。人們認為它們在滿洲濕地繁殖——目前還沒有人確切知道——它在菲律賓越冬,問題可能就在這裡,因為它所青睞的幾處濕地已被「開墾」。

作為一種正在衰落的濕地鳥類,鶯絕非孤例。秋天,海明森 (Hemmingsen) 看到多達 10,000 隻豆鵝經過。即使有觀察小組輪流監測可見的遷徙,我們的最佳計數也只有 4000 只左右。我們目睹的東方白鸛和鶴的飛行數量也無法與海明森記錄的峰值數量相匹配。成群的苔原(比威克)天鵝 哥倫比亞天鵝 越來越小,越來越少──最近秋天已經沒有了。北方針尾鴨 (Northern Pintail Anas acuta) 並不常見,拉圖什 (La Touche) 認為這種鴨子「可能是數量最多的大型鴨子」。貝爾潛鴨(Baer's Pochard Aythya baeri)——根據拉圖什的說法,秋季「極其豐富」——現在充其量是不常見的。拜永秧雞顯然比較稀有,歐亞白頂鶴也同樣稀有 富利卡·阿特拉、 小杓鷸、帕拉斯草鶯和日本沼澤鶯。

貝加爾湖青色 台灣鴨 也許值得特別一提;它的人口並沒有減少或直線下降,而是崩潰了。它在東亞曾經很豐富——海明森曾經在北戴河看到1000-2000隻的鳥群。現在,這種現像在其分佈範圍的大部分地區都已不常見:自 1985 年我們重新開始研究以來,在北戴河僅記錄到了 15 只個體。墜機原因尚不清楚。主要原因可能是狩獵。

濕地鳥類減少的另一個異常現像是桑德林 白鷸。一般來說,是因為覆蓋範圍增加,還是其他地方棲息地消失? ——我們發現濱鳥的數量比海明森報道的還要多。桑德林則不同。海明森認為「成群結隊,比如說 30-100 隻」;但我們最近的記錄很少,只有個位數。我想知道它是否是其越冬地干擾的受害者,對於「我們」的族群來說,越冬地主要位於東南亞沿海地區。作為海灘專家,桑德林可能輸給了為熱愛陽光的遊客建造的度假村。

靠近北戴河的沿海濕地受到了影響。海明森報告了歐亞蠣鷸 奧氏血魚 六月,在北戴河的一個河口,這是一個瀕臨滅絕的東方物種。也許他們繁殖了;但不再是了。事態的發展甚至讓更具韌性的小燕鷗 白胸燕鷗 空間緊迫。

鎮南海岸沿線,魚池、蝦池如野火般蔓延。它們所取代的鹽沼原本是鶴、鵝和大鴇等鳥類的棲息地。從我們的幾次訪問來看,所有這些鳥類仍然定期在灤河口夾在蝦池之間的鹽沼和粗糙的田野上停留。

該地區還擁有(現在,2005 年:據報導該地區已被摧毀)大約有一百對正在繁殖的桑德斯鷗。桑德斯鷗的數量只有 2000 隻左右,是中國特有的繁殖鳥類,直到 1987 年才首次發現其繁殖地,桑德斯鷗一定是中國最受威脅的脊椎動物之一。據了解,除灤河外,它僅在三個地點繁殖:滿洲南部沿海、黃河三角洲和上海北部。每一個項目中,蝦池和其他開發案都在遷入。最大的棲息地可能已經被一座水庫摧毀了,該水庫是為了灌溉所謂的野生動物保護區的田地而建造的。

該地區還擁有(現在,2005 年:據報導該地區已被摧毀)大約有一百對正在繁殖的桑德斯鷗。桑德斯鷗的數量只有 2000 隻左右,是中國特有的繁殖鳥類,直到 1987 年才首次發現其繁殖地,桑德斯鷗一定是中國最受威脅的脊椎動物之一。據了解,除灤河外,它僅在三個地點繁殖:滿洲南部沿海、黃河三角洲和上海北部。每一個項目中,蝦池和其他開發案都在遷入。最大的棲息地可能已經被一座水庫摧毀了,該水庫是為了灌溉所謂的野生動物保護區的田地而建造的。

可能還有另一個災難故事正在上演:三峽大壩,一個誇張的工程,將淹沒一個被報紙報道為與大峽谷相比較的地區。大壩將擾亂長江的水流,威脅長江特有的物種,如長江豚和中華鱘。河口泥灘將受到影響。夏季淹沒河谷大型湖泊的洪水可能會減少。

這些湖泊對水禽來說非常重要,尤其是在冬天,鄱陽湖的一角可能棲息著超過一百萬隻鴨子、鵝、天鵝和鶴,其中包括西伯利亞鶴。自上世紀末以來,中國的越冬西伯利亞鳥類在鳥類學中“消失”,但於1980年至1981年的冬天在鄱陽被重新發現。保護區建立了,更多的鳥類來到這裡,享受免受猖獗狩獵的保護。鄱陽白鶴的數量大幅增加,從首次發現時的 140 隻增加到最高峰的 2900 隻。它們的繁榮可能是短暫的。

人口下降的另一個原因是森林砍伐。然而,很難判斷其影響是否與濕地破壞類似,因為根據過去和最近的記錄來衡量北戴河鳴禽的族群變化比水禽更困難。但在一個案例——西伯利亞藍知更鳥——證據似乎是無可辯駁的:數量已經嚴重下降。罪魁禍首很可能是:冬季範圍內的熱帶森林遭到破壞。

海明森在談到藍知更鳥時寫道:“春天……這個物種大約在五月中旬及之後一段時間聚集在北戴河。”有時,它們「多到難以計數」。儘管海明森在秋天看到的樹木相對較少——因為樹葉更茂密——但有報導稱北戴河的樹木大量落下。一位駐北京的觀鳥傳教士GD Wilder 相當隨意地說:「[1923 年] 9 月10 日,西伯利亞藍貓…出現在田野和長滿青草的山坡上,周圍有成千上萬的小松樹……”光是最近的一個春天,數字就很高,一天達到 250 隻——令人印象深刻,但不是蜂擁而至;否則很容易計算。秋季的數量並不多。現在懷爾德所描述的秋天似乎是一個遙遠的幻想。

在東南亞越冬的西伯利亞藍知更鳥特別容易受到森林砍伐的影響,因為至少在泰國,它更喜歡低地森林,而這些森林總是最先被砍伐的。其他移民肯定也遭受同樣的痛苦。 [2004 年初新增:有報導稱,為了滿足中國對木材的需求,印尼(和其他地方)的採伐量增加,問題肯定會惡化。]

這場大屠殺似乎將蔓延到北部,蔓延到許多移民的繁殖地。隨著蘇聯的解體,以及更開放的俄羅斯對收入的渴望,韓國、日本和其他公司迅速提供了幫助,以砍伐西伯利亞森林。

可能用不了多久,森林砍伐的影響就會在北戴河的移民數量上更明顯地顯現出來。幾十年之內,我們今天所知的移民可能會成為一個不可能實現的夢想,就像拉圖什時代的移民對我們現在來說一樣。

狩獵加劇了棲息地的喪失和破壞。拉圖什報導,上世紀末,白鷺因捕獵羽毛而遭到毀滅性打擊。在他工作後的幾十年裡,它們的數量可能有所恢復,但幅度很小,這表明狩獵仍然造成了損失。 [2005年更新:白鷺在沿海地區變得相當普遍,現在北戴河有大量白鷺。]狩獵無疑對水禽產生了很大的影響——它可能摧毀了貝加爾水鴨的種群,因為貝加爾水鴨有密集飛行的習慣具有可預測的日常運動模式的羊群。也許它也影響了大鴇以及許多其他鳥類,它們同樣以比以前更小的群體飛過北戴河。

1993年2月號的一篇文章 中國環境報 標題是「獵人屠殺了博陽的野鳥」。文章稱,每年冬天,鄱陽縣有30萬隻鴨子被毒餌殺死。 (反過來,吃鴨子中毒死亡的情況也很常見。)水禽也會被射殺,儘管這是「國家禁止的」。它們在市場上出售,其中一些——特別是稀有的、據稱受保護的物種——運往中國南部和香港的餐館。每隻鴨子的市價約為$3。每隻鵝的價格幾乎為 $10 美元,而天鵝的價格約為 $30 美元——比許多中國人一個月的收入還要高。

北戴河移民始終保持警惕,反映出他們面臨的狩獵壓力。在鎮上的調查過程中,我們看到海鷗和畫眉鳥為了食物而被射殺,其他一些鳥類純粹為了運動而被射殺,還有孩子們用彈弓射向鶯、藍尾鳥、紅尾鳥和其他射程內的鳴禽。 [2005 年更新:由於教育和執法工作,現在很少看到這種情況。]

誘捕現象十分普遍;儘管有法律禁止,雀類、鹀類和北蒼鷹仍被困在北戴河。 [2005年更新:仍然有一些誘捕行為,但這遠沒有那麼明目張膽,因為當地政府已經做出了一些努力來抓捕和懲罰鳥類誘捕者。]

通常,很難衡量誘捕的影響。但來自泰國的一個例子,涉及途經北戴河的遷徙鳴禽,顯示這可能是毀滅性的。 1960 年代末,在對曼谷野生動物市場進行調查時,黃鶺鴒 黃鰍 鹀和黃胸鹀數量較多,總數分別為 16,721 隻和 87,209 隻。然而,1987 年 12 月至 1988 年 12 月的重複調查並沒有發現任何一個物種。可能的原因是被困在它們的公共棲息地。

雖然這兩個物種在北戴河仍然很常見,但它們的數量絕不像拉圖什所描述的那麼豐富(黃鶺鴒成群結隊地飛過;黃胸鹀在莊稼地裡成群結隊)。誘捕也可能是這裡的原因。也許許多人曾經——現在仍然——被困在中國南方,那裡人們普遍吃被稱為「米鳥」的黃胸鹀。也許在泰國捕獲並出售的鶺鴒和鹀鷚包括經過北戴河的鳥類。

2024 年更新:黃胸鹀現已被列為極度瀕危物種,因為數量急劇下降。

在東亞許多地區,殺蟲劑的使用常常是隨意而粗心的,而這些殺蟲劑很可能也為野鳥帶來了可怕的後果。據我所知,還沒有關於它們對中國鳥類種群影響的嚴肅研究——中國的《寂靜的春天》還沒有被寫出來。因此,就像在尋找北戴河外來人口減少的原因時一樣,我們只能猜測何時是農藥造成的。也許,它們是黑鳶數量急劇下降的主要原因 遊走米爾烏斯 和魯克斯。

北戴河育鳥與老峰

在經濟衰退、厄運和憂鬱之中,也有一些正面的跡象。在越來越多觀鳥者到來的鼓勵下,北戴河政府在水庫旁建立了一個小型保護區。目前,保護區內只有一些沼澤地,如果一切按計畫進行,保護區將變成一個潟湖,遊客中心可以俯瞰該保護區。 [2005年更新:仍希望這能成功;請參閱 2005 年 5 月造訪的文章。]蓮花山西部已指定另一個保護區,為連綿起伏、樹木繁茂的公園綠地提供一定的保護。而且,部分由於我們的觀察,灤河口現在已成為保護區。 [哈! ——據說。我聽到了這個;後來得知它已被新魚池的開發大部分毀掉了。]

在經濟衰退、厄運和憂鬱之中,也有一些正面的跡象。在越來越多觀鳥者到來的鼓勵下,北戴河政府在水庫旁建立了一個小型保護區。目前,保護區內只有一些沼澤地,如果一切按計畫進行,保護區將變成一個潟湖,遊客中心可以俯瞰該保護區。 [2005年更新:仍希望這能成功;請參閱 2005 年 5 月造訪的文章。]蓮花山西部已指定另一個保護區,為連綿起伏、樹木繁茂的公園綠地提供一定的保護。而且,部分由於我們的觀察,灤河口現在已成為保護區。 [哈! ——據說。我聽到了這個;後來得知它已被新魚池的開發大部分毀掉了。]

在經歷了 20 世紀 60 年代和 1970 年代的大規模環境破壞之後,整個中國正在採取一些旨在改善狀況的措施。其中有一道“綠牆”,即沿海種植園的防護林。雖然,就像北戴河一樣,綠牆有時會覆蓋鸛、鶴、鵝和大鴇休息的土地,但它無疑是遷徙鳴禽的重要棲息地,以前它們在長長的綠地中可能找不到什麼遮蓋物。海岸。

植樹造林改變了北戴河。懷爾德在 1920 年代撰文稱,隨著新的種植園的出現,東方斑鳩開始築巢 東方鏈球菌, 啄木鳥(灰頭 啄木鳥 和更大的斑點 大鯽), 大奶 大山雀、 和黑枕黃鶯 黃鷂 ——所有這些在今天都很常見。最近,中國池鷺 酒神鳥 海明森在水庫旁的種植園裡建立了一個殖民地,即使作為遊客,海明森也沒有被記錄下來。 [2005年更新:現在有大量繁衍生息的白鷺,包括大白鷺、小白鷺和黑冠夜鷺。]但即使是鎮上最好的樹林也有人造的感覺,並且繁殖的多樣性很低鳥類。為了獲得更多的天然林地,我們不得不把目光投向更遠的地方。

植樹造林改變了北戴河。懷爾德在 1920 年代撰文稱,隨著新的種植園的出現,東方斑鳩開始築巢 東方鏈球菌, 啄木鳥(灰頭 啄木鳥 和更大的斑點 大鯽), 大奶 大山雀、 和黑枕黃鶯 黃鷂 ——所有這些在今天都很常見。最近,中國池鷺 酒神鳥 海明森在水庫旁的種植園裡建立了一個殖民地,即使作為遊客,海明森也沒有被記錄下來。 [2005年更新:現在有大量繁衍生息的白鷺,包括大白鷺、小白鷺和黑冠夜鷺。]但即使是鎮上最好的樹林也有人造的感覺,並且繁殖的多樣性很低鳥類。為了獲得更多的天然林地,我們不得不把目光投向更遠的地方。

從北戴河出發,經過三個小時的小巴之旅,我們到達了老峰,這是一個以海拔 1424m 的山頂為中心的風景區,是城鎮附近山脈的最高點。通往該地區的峽谷覆蓋著落葉林地——在經過污染工廠和途中灌木叢生的山坡之後,這是一個受歡迎的景象——而在其上方的盆地中,有一個針葉樹種植園,兩側是崎嶇的山峰和更多的口袋

從北戴河出發,經過三個小時的小巴之旅,我們到達了老峰,這是一個以海拔 1424m 的山頂為中心的風景區,是城鎮附近山脈的最高點。通往該地區的峽谷覆蓋著落葉林地——在經過污染工廠和途中灌木叢生的山坡之後,這是一個受歡迎的景象——而在其上方的盆地中,有一個針葉樹種植園,兩側是崎嶇的山峰和更多的口袋

我去過四次,都是在春末,那時五種杜鵑——大鷹——的歌聲 杜鵑, 常見的 坎諾魯斯, 東方 飽和 C. saturatus, 較小 長頭 C. policephalus 和印度人 小鰭魚 ——環山而過,環頸 雉雞 和科克拉斯 大葉紫金龜 雉雞在茂密的樹叢中鳴叫,毛冠麻雀 鯽魚 樹林間的鷹蟲。

其他可能或肯定在當地繁殖的鳥類包括中國五子雀 絨毛西塔, 東方冠鶯、中華葉鶯 四川蜱 (最近發現的物種,主要產於中國中部),Elisae's Flycatcher 蠅蛆 (以前被認為是具有這個通用名稱的物種;後來與水仙鶲混為一談 水仙花 因為某些原因;最近被有洞察力的人們視為獨立的物種,儘管不幸的是它的名字單調乏味綠背鶲[為什麼-哦-為什麼-哦-為什麼偉大的鳥類必須被賦予致命的沉悶的名字?]) - 或中國鶲- 西伯利亞藍知更鳥,費埃鶇 鶇, 畫眉 毛皮鶇、達烏爾紅鴝和黃喉鹀。其中一些超出了其公佈的繁殖範圍。從鳥類學角度來看,這些山丘很少被探索過。

盆地裡有一塊經風化侵蝕的花崗岩露頭,從這裡可以看到陡峭、樹木繁茂的峽谷,一直到長城遺址的山麓,再到遠處的沿海平原,在薄霧中灰色而模糊。在春日明媚的日子裡,站在這裡,聽著森林再生的歌聲和呼喚,我找到了對未來的希望。儘管衰退可能是不可避免的,但也不能不受控制。這是值得努力的,努力提高認識並刺激更好的執法,並鼓勵建立儲備。

盆地裡有一塊經風化侵蝕的花崗岩露頭,從這裡可以看到陡峭、樹木繁茂的峽谷,一直到長城遺址的山麓,再到遠處的沿海平原,在薄霧中灰色而模糊。在春日明媚的日子裡,站在這裡,聽著森林再生的歌聲和呼喚,我找到了對未來的希望。儘管衰退可能是不可避免的,但也不能不受控制。這是值得努力的,努力提高認識並刺激更好的執法,並鼓勵建立儲備。

秋季的遷徙就像春天的鏡像,晚春的鳥類通常最早出現在秋季,早春的鳥類要到秋末才經過。這個圖像遠非準確:並非所有鳥類都符合這種相反的出現順序,而且不同物種的豐度通常在不同季節有所不同(當它們出現這種情況時,秋季的數量總是更高)。而且,秋天的時間也比較長。春季的通道最多持續四個月,而秋季的通道則持續五個多月。

北戴河初秋遷徙

即使最後一批春季候鳥向北遷徙,秋季第一批南下的鳥類也可能出現。 1991 年 6 月 17 日——我最近一次在「春天」來到這個小鎮——我看到了 17 隻白翅雀 白翅石蠶 和六個鬍鬚 雜交種 燕鷗向南飛過水庫。懷爾德和海明森還在六月看到了白翅燕鷗向南飛行。 1944年,海明森的6月記錄拉開了7月大批人潮的序幕:7月11日上午9點到10點30分,「成群結隊的人從秦皇島灣源源不斷地湧來…肯定有數百隻。”同樣的情況在晚上和其他許多天再次出現。如果考慮到沒有進行任何觀察的時間,肯定已經過去了數千人。這些可能是失敗的育種者。

即使最後一批春季候鳥向北遷徙,秋季第一批南下的鳥類也可能出現。 1991 年 6 月 17 日——我最近一次在「春天」來到這個小鎮——我看到了 17 隻白翅雀 白翅石蠶 和六個鬍鬚 雜交種 燕鷗向南飛過水庫。懷爾德和海明森還在六月看到了白翅燕鷗向南飛行。 1944年,海明森的6月記錄拉開了7月大批人潮的序幕:7月11日上午9點到10點30分,「成群結隊的人從秦皇島灣源源不斷地湧來…肯定有數百隻。”同樣的情況在晚上和其他許多天再次出現。如果考慮到沒有進行任何觀察的時間,肯定已經過去了數千人。這些可能是失敗的育種者。

灰椋鳥 灰白椴樹 7 月期間也可能大量湧入:“1914 年 7 月 4 日,”拉圖什寫道,“數千人從東北飛向西南。”濱鳥開始向南遷徙——海明森從六月下旬開始記錄到麻鷸——而普通黑頭鷗則返回海岸。但整體而言,7 月的生產力相對較低。而且,隨著夏季遊客的大量湧入,現在並不是遊覽北戴河的最佳時間。

1987年7月,兩名丹麥觀鳥者在北戴河度過了四天。一天早上,他們在黎明前起床,到達了濱鳥的主要棲息地之一——沙灘,發現這裡不是鳥群,而是人,總共有1375 只(不過,丹麥人確實看到一隻遺鷗飛過) )。

八月底比較好;我最早到的是20號,這對觀鳥者來說,大致標誌著北戴河秋天的開始。濱鳥數量眾多,一天早上,沙灘上記錄了 34 種 2000 隻濱鳥。此時可能更常見的白翅燕鷗正在經過。叉尾雨燕數量眾多:1986 年 8 月 30 日下午,超過 4,000 隻叉尾雨燕南下。樹林裡,有零星的候鳥鳴禽。北極鶯、厚嘴鶯、亞洲天堂鶯、黃腰鶯、灰紋鶯 灰鶲, 陰暗面 西伯利亞海膽,和亞洲棕色 闊口鷸 捕蠅器在夏季茂密的樹葉中尋找昆蟲。森林鶺鴒 印度石斛夏季鳥類在迪斯可臀部旋轉,開始從樹林中撤退。

九月鳴鳥和猛禽航班

九月初,悶熱的夏季天氣即將結束,值得慶幸的是,夏季遊客也蜂擁而至。鴴鷸的種類和數量已經在下降,但仍然良好;他們可能包括一兩個諾德曼的小青腿。遺鷗——絕大多數是忙著尋找螃蟹的幼鳥——從月中旬開始就可以看到。

九月初,悶熱的夏季天氣即將結束,值得慶幸的是,夏季遊客也蜂擁而至。鴴鷸的種類和數量已經在下降,但仍然良好;他們可能包括一兩個諾德曼的小青腿。遺鷗——絕大多數是忙著尋找螃蟹的幼鳥——從月中旬開始就可以看到。

幾乎在九月的任何一個早晨,您都會早早前往沙灘,您會注意到鳴禽向南飛去。它們通常從海上飛來,穿過沙灘,飛向城鎮上空,而不是繞著北戴河所在的三角形土地飛行,而是抄近路。這裡有成群的黃鶺鴒,成群的理查鷚 黎氏花, 橄欖樹鷚 紅花、彩旗和一群群跳躍的栗色側翼繡眼鳥 紅胸大葉藻。雖然叫聲可以幫助您識別和找到鳥類,但許多鳥類卻未被發現。白眼鳥似乎是隱形大師——北戴河的隱密遷徙者。很多時候,我聽到了很多呼喚聲,但抬頭看到的卻只是藍天。

像這樣的鳴禽飛行在春天就不太明顯了,唯一一致的報道來自鷹岩,這是一個俯瞰沙灘的岩石岬角。秋天的北戴河,無論你在哪裡,都可以看到、聽到鳥鳴聲。除了飛越沙灘之外,鳴禽還會沿著城鎮南海岸飛越蓮花山,從那裡您可以看到遠處的鳥群在平原上空向南遷徙。即使您騎自行車穿過城鎮的街道,或步行穿過飯店的庭院,您也可能會注意到鳴禽經過。可能還有燕鷗、海鷗、濱鳥和猛禽。

像這樣的鳴禽飛行在春天就不太明顯了,唯一一致的報道來自鷹岩,這是一個俯瞰沙灘的岩石岬角。秋天的北戴河,無論你在哪裡,都可以看到、聽到鳥鳴聲。除了飛越沙灘之外,鳴禽還會沿著城鎮南海岸飛越蓮花山,從那裡您可以看到遠處的鳥群在平原上空向南遷徙。即使您騎自行車穿過城鎮的街道,或步行穿過飯店的庭院,您也可能會注意到鳴禽經過。可能還有燕鷗、海鷗、濱鳥和猛禽。

白翅燕鷗和須燕鷗經常抄近路飛越沙灘和穿越城鎮。許多濱鳥也是如此——其中一些可能從北方飛來,降落在沙灘上,然後繼續它們的旅程。九月飛翔的濱鳥中最突出的是灰頭田鳧 灰白雲螺。它們在地面上的顏色相當單調,但在飛行時卻是大膽的黑白,它們可能會成群地飛行,數量可能有 200 隻或更多,早上的飛行總數可能有兩三千隻。在這樣的早晨,多達數百隻 Pied Avocet 反蝽 也可能飛向南方。而且,幾乎可以肯定的是,還會有花斑鷂,它們在清晨低空飛行,到中午時它們的數量通常會減少,但偶爾會增加,因為它們利用熱氣流在平原上空高空飛行。

北戴河觀賞斑鷂以及飛越該地區的許多其他鳥類的最佳地點是蓮花山。從1986年8月20日到11月20日,我們的調查團隊花了854小時監測來自山上的可見遷徙。包括未知的鷚、鷚等,我們總共記錄了 160 個品種的 262,970 隻鳥類——平均每小時通過率略高於 300 只(不過,有一些很長很長、幾乎沒有鳥類的時間) 。

北戴河觀賞斑鷂以及飛越該地區的許多其他鳥類的最佳地點是蓮花山。從1986年8月20日到11月20日,我們的調查團隊花了854小時監測來自山上的可見遷徙。包括未知的鷚、鷚等,我們總共記錄了 160 個品種的 262,970 隻鳥類——平均每小時通過率略高於 300 只(不過,有一些很長很長、幾乎沒有鳥類的時間) 。

九月,蓮花山特別適合觀賞猛禽,包括斑鷂、東方小鷂和白喉針尾鷂 Hirundapus caudacuta。 針尾似乎被磁鐵吸引到了山上。天氣好的時候,成群的鳥群從北方飛來,滑翔、盤旋,然後翅膀拍打幾下,像高速子彈一樣從頭頂呼嘯而過,消失在南方。

與春季一樣,可見遷徙的強度也會波動。蓮花山的日子可能很悠閒,天空似乎空無一人,除了常住的燕子,很可能還有北方的愛好 隼 俯衝追蜻蜓。更常見的是,有一些段落可以看到。而且,偶爾也會有波浪日。

就像 1986 年 9 月 12 日那樣的日子。黎明時分,我們到達了觀察點。已經有鳴禽飛過來了。還有花斑鷂,低空滑過山脊,掠過下面的田野。天空晴朗,西風徐徐,天氣暖和了,鷂爬得更高了。它們的數量不斷增加,很快地它們就成群結隊地從頭頂上湧過,或者像水壺一樣在山丘和平原上空翱翔。東部沼澤鷂(條紋鷂) 螺螄, 黑鳶, 鳳頭蜜鵟 黑嘴鱸,和日本雀鷹 紅鷹 是其他加入水壺的猛禽之一,然後,在我們上方的高處,向南滑翔。 [我們看到的幾隻飛過北戴河的猛禽都缺少大塊的飛羽,就像照片中的鳳頭蜜禿鷹一樣——因為它們是被槍殺的?]東方普拉廷科的叫聲響起,刺耳而急切;收到它們的警報後,我們掃視天空尋找它們的羊群,它們可能在上升的空氣中旋轉,有時看不見——就像白眼鳥一樣,它們很難被發現。

就像 1986 年 9 月 12 日那樣的日子。黎明時分,我們到達了觀察點。已經有鳴禽飛過來了。還有花斑鷂,低空滑過山脊,掠過下面的田野。天空晴朗,西風徐徐,天氣暖和了,鷂爬得更高了。它們的數量不斷增加,很快地它們就成群結隊地從頭頂上湧過,或者像水壺一樣在山丘和平原上空翱翔。東部沼澤鷂(條紋鷂) 螺螄, 黑鳶, 鳳頭蜜鵟 黑嘴鱸,和日本雀鷹 紅鷹 是其他加入水壺的猛禽之一,然後,在我們上方的高處,向南滑翔。 [我們看到的幾隻飛過北戴河的猛禽都缺少大塊的飛羽,就像照片中的鳳頭蜜禿鷹一樣——因為它們是被槍殺的?]東方普拉廷科的叫聲響起,刺耳而急切;收到它們的警報後,我們掃視天空尋找它們的羊群,它們可能在上升的空氣中旋轉,有時看不見——就像白眼鳥一樣,它們很難被發現。

從下午三點左右開始,航速逐漸變慢,但一直持續到黃昏,當天的值班持續了 12 個小時以上。向南飛過的鳥類統計包括一隻魚鷹 鰍; 15 隻黑風箏; 170 鳳頭蜜鵟; 4 架東部沼澤鷂; 10 隻歐亞紅隼 紅隼; 9 北方愛好; 34 阿穆爾獵鷹 山隼; 152 隻日本雀鷹和 27 隻北雀鷹; 791 東方 Pratincoles; 1015 家燕 燕雀; 45 黃色,121 白色 白葉輪 和兩個灰色 灰黴病菌 鶺鴒; 174 理查德氏, 31 橄欖樹和 15 紅喉 鹿花 鷚; 9 灰燼迷你車 叉周角鷸; 14 黑枕金鶯; 18 黑鴉 大尾蠈; 11 普通朱雀;其中最出色的是 2957 隻花斑鷂。

藉助這一天,我們在 1986 年秋季進行的調查中發現了數量驚人的 14,534 隻花鷂。這個數字很可能代表了該物種在世界人口中的很大比例。

冷鋒驅動北戴河秋季遷徙

十月初,秋天已經來臨。樹葉從綠色變成棕色,只有最頑強的游泳者才能在幾週前擠滿遊客的海灘上游泳。候鳥的種類可能在這個時候達到頂峰,儘管不像春天那麼劇烈,而且鳥類的種類也有所不同。

本季第一股冷鋒可能在本月初抵達,從西伯利亞席捲至中國南方。

在這些前沿之前,可能會有鳴禽墜落。它們在天氣晴朗、風平浪靜的日子裡抵達,那時空氣變得朦朧,而且變得更加朦朧,可見的遷徙可能已經陷入停滯,並在樹林和沿海溝壑中綻放。

我記得在這樣一個秋天的日子裡,我沿著燈塔角走下去,沿著小路快步走到岬角,可能只需要十分鐘。那裡到處都是鳥兒,特別是帕拉斯葉鶯,似乎每棵樹上都有它們,而且常常成群結隊地活躍。據我估計,至少有六十人;其他鳥類包括 13 隻紅腹藍尾鶯、7 隻暗色鳥、4 隻拉德鶯、6 隻黑眉蘆葦鶯和一隻藍喉鳥 斯維西絲蟲.

我記得在這樣一個秋天的日子裡,我沿著燈塔角走下去,沿著小路快步走到岬角,可能只需要十分鐘。那裡到處都是鳥兒,特別是帕拉斯葉鶯,似乎每棵樹上都有它們,而且常常成群結隊地活躍。據我估計,至少有六十人;其他鳥類包括 13 隻紅腹藍尾鶯、7 隻暗色鳥、4 隻拉德鶯、6 隻黑眉蘆葦鶯和一隻藍喉鳥 斯維西絲蟲.

綜合大家當天在北戴河的觀鳥記錄,黃葉鶯有395隻;其他湧入的鳴禽包括68 隻紅腹藍尾鶯、28 隻黃眉鶯、45 隻暗色鶯和18 隻拉德鶯、5 隻帕拉斯草鶯、35 隻黑眉蘆葦鶯、42 隻帕拉斯蘆鹀 帕拉西鰍, 43 小 E. pusilla, 和 5 黃眉 黃花桉 彩旗。

同月晚些時候,當另一場冷鋒逼近時,我看到三十隻紅腹藍尾魚在六棵樹及其周圍覓食。那天,我們在鎮上總共記錄了 210 隻藍尾魚;還有 21 隻暗鶯、285 隻帕拉斯蘆鹀、216 隻鄉村鹀和 86 隻黃喉鹀。

同月晚些時候,當另一場冷鋒逼近時,我看到三十隻紅腹藍尾魚在六棵樹及其周圍覓食。那天,我們在鎮上總共記錄了 210 隻藍尾魚;還有 21 隻暗鶯、285 隻帕拉斯蘆鹀、216 隻鄉村鹀和 86 隻黃喉鹀。

我不知道為什麼鳥兒會在這麼好的天氣下飛來。也許食蟲動物尤其會聚集起來,利用溫和的條件,在繼續遷徙之前養肥。也許他們聚集在海岸,為即將到來的天氣做好準備。

鋒面帶來遷徙天氣。通常,它們之後會出現典型的秋季遷徙條件,伴隨著凜冽的北風或西北風和晴朗的天空。一旦鋒線穿過,蜂擁而至的鳴禽就消失了。

當當前線到來時,雲層滾滾而來。空氣通常是靜止的。然後,風開始吹,溫度下降。如果是深秋,可能會下雨,甚至下雪。我記得早上在飯店房間度過,等待天氣好轉,這樣我們就可以出去觀察可見的遷徙;有一天,從早上下雨到下午晚些時候,我們站在一家有遮蔽的酒店陽台上,觀看數千隻豆雁和北方田鳧 瓦內魯斯 他們順著風向南衝去。

雨停後,就該快速前往觀察點了。智神葉鶯墜落後席捲而來的鋒面帶來了降雨。鋒線在夜間到達,天亮後雨仍在下。雨停了之後,我們就離開了飯店。

當我們走出大廳時,我們抬頭看到了一群 70 隻灰鷺 灰鷺 過去。更多的鳥群沿著東海岸席捲而下,通常從海上低空到達東北部,當它們遇到低矮的懸崖時,就像微風中飄揚的樹葉一樣散開,氣流在狂風中旋轉。在兩個小時內,它們幾乎不間斷地經過:我們記錄了 1417 隻灰鷺,還有 135 隻大鸕鶿 碳鸕鶿,還有兩隻白琵鷺 白樺。然後,一切平靜了。中午時分,天空放晴,遷徙再次激增——當天的大部分是21隻黑鸛、26只北雀鷹、21只北蒼鷹、427只禿鷹 鵟, 1167 達烏鴉, 和 2693 烏鴉或食腐烏鴉 烏鴉冠 在寒冷的下午從蓮花山看到的。

儘管隨著冷鋒的通過,似乎幾乎肯定會出現一波“移民潮”,但我們還無法預測主要物種是什麼。也許除了 1986 年秋天的一個波浪日。

10月21日,與我們一起度過了大部分秋天的年輕中國鳥類學家陶宇來到蓮花山觀察點,他說:“昨天,我做了一個夢——很多烏鴉。”我們已經記錄了成群的食腐烏鴉、白嘴鴉和道烏鴉。隨後還有更多的事情發生。下午,它們向南流去,這一天成為近年來最好的烏鴉日,共有3175隻達烏鴉和9243隻烏鴉或腐肉烏鴉。我們等待著濤的另一個夢想——最好是像朱鹮這樣的稀有物品 日本鳳梨 或鳳頭鴨 Tadorna cristata。 但無濟於事。

波浪並不總是立即跟隨前沿。有一次,當一陣殘酷的西風從平原上吹來時,我們三個人花了幾個小時掃描天空,盡可能地躲避。我們幾乎什麼也沒看到:八小時內看到了三隻北方蒼鷹和三十一隻鳴禽。第二天,刮東北風,情況較好——有 777 隻北田鳧和 713 隻白嘴鴉或腐肉烏鴉。但到了第三天,我們看到了我們一直希望的那種波浪。雖然不是很大的波浪,但卻令人難忘。

1990年11月2日有微風,上午主要為東北風,下午為南風。早上很閒。從午餐時間開始,鶴就開始飛過。有紅冠鳥、普通鳥和兜帽鳥,數量都很少。還有西伯利亞鳥,當我們發現它們時,它們是旋轉的、遙遠的白色鳥,在城鎮北部的熱氣流中翱翔。隨著高度的增加,它們排成V字形,不慌不忙但目標明確地飛入微風中。許多人靠近了山丘,山上再次響起了它們刺耳的叫聲。景象和聲音都很神奇。這一天總共產生了 389 隻西伯利亞鳥,超過了過去四年每年的季節總數,也是自 1945 年 3 月 28 日海明森記錄的 545-645 只西伯利亞鳥以來北戴河單日最多的一天。

東方鸛,北戴河觀鳥年壓軸戲

每出現一次冷鋒,冬天就更近了一步。新鮮的風從樹上吹落葉子,空氣變冷,鳥類的組合也發生了變化——鋒面到來之前存在的一些物種在這一年中可能不會再出現;隨著鋒面的過去,可能會有其他物種在秋天首次出現。

到了十一月初,冬季遊客又回來了,觀鳥活動也與三月的情況有些相似。但是,在大多數情況下,它比三月更加多樣化和有趣。此時常見的鳥類中值得注意的是東方白鸛。

直到我第一次讀到海明森關於北戴河的報告,我才知道遠東有白鸛。從他的描述來看,它與我在訪問以色列時認識的歐洲白鸛不同 鸛鸛。 例如,它的喙更長,呈黑色,而不是紅色。海明森在春天只看到一些,但在深秋時它們可能會很多:曾經有 1000-1500 隻的一群在城鎮附近停留了兩天,可能是被霧擋住了;在另一個秋天,他估計一天能看到 1000-4000 隻鳥。

到1986 年秋天,人們越來越認識到東方白鸛是與其歐洲近親不同的物種——除了長長的黑嘴之外,它體型更大,行為也不同——對其冬季棲息地和繁殖區的調查表明,世界白鸛數量為最多,只有1200隻。由於狩獵和農業化學品中毒,它在上世紀在日本很常見的繁殖鳥中已被滅絕。 20 世紀 40 年代,這種疾病在韓國“當地很常見”,但到了 80 年代末,它的種鳥已經消失。只有西伯利亞東南部和中國阿穆爾河流域附近的鄰近地區仍然有繁殖鳥類,它們大多沿著長江流域越冬,與白鶴共享棲息地。

1985 年春季我們只記錄了 12 個——但是,由於 Hemmingsen 的記錄,我希望我們可以在 1986 年秋季看到良好的數字。我的希望已經實現了。

鸛鳥從十月開始出現,這種巨大的鳥類在威嚴上可與鶴相媲美,但它們卻默默地滑過,它們不是呈V字形,而是隨機成群。 10 月 29 日黃昏,一大群鳥從陰暗中滑翔出來,低空掠過我們西邊的平原:我們估計有 280 隻鳥,約佔已知世界人口的四分之一。 11 月,我們看到了更多巨型鳥群,很快就突破了 1200 隻大關,最終達到了 2729 隻東方白鸛——這可能是當時還活著的大多數鳥類。

鸛鳥從十月開始出現,這種巨大的鳥類在威嚴上可與鶴相媲美,但它們卻默默地滑過,它們不是呈V字形,而是隨機成群。 10 月 29 日黃昏,一大群鳥從陰暗中滑翔出來,低空掠過我們西邊的平原:我們估計有 280 隻鳥,約佔已知世界人口的四分之一。 11 月,我們看到了更多巨型鳥群,很快就突破了 1200 隻大關,最終達到了 2729 隻東方白鸛——這可能是當時還活著的大多數鳥類。

但是,雖然我們的統計數量比估計的世界人口增加了一倍多——達到大約3000 只——但我們沒有看到任何鳥群數量接近1500 只,也沒有看到像海明森那樣超過1000 只的日子。此後,我們在一個秋天未能捕獲超過 2000 隻東方白鸛。儘管對該物種採取了保護措施(至少在紙面上),但狩獵、棲息地破壞、幹擾和中毒仍在繼續;它們可能導致自1986年以來人口下降,而且隨著更多濕地被"開墾",人口數量可能會進一步下降。

11月,整體遷徙量進入下降趨勢。小鎮周圍可能有有趣的鳥類——也許是成群的波西米亞鳥類 家蠶 或日語 粳稻 太平鳥和一兩隻英俊的古爾登施塔特紅尾鴝 紅腹鳳凰。遊覽灤河和大清河非常有機會看到鶴、鵝、大鴇以及灰伯勞 拉尼爾斯挖土機,已故的桑德斯海鷗,也許還有遺鷗。

11月,整體遷徙量進入下降趨勢。小鎮周圍可能有有趣的鳥類——也許是成群的波西米亞鳥類 家蠶 或日語 粳稻 太平鳥和一兩隻英俊的古爾登施塔特紅尾鴝 紅腹鳳凰。遊覽灤河和大清河非常有機會看到鶴、鵝、大鴇以及灰伯勞 拉尼爾斯挖土機,已故的桑德斯海鷗,也許還有遺鷗。

嚴格來說,秋季遷徙將持續到11月下旬;然後,常規飛行將停止,只有當惡劣天氣的遷徙將鳥類從冰凍的北方推下時,新的鳥類才有可能到達。

但這段話並沒有就此消失。 11月,北戴河鳥年的壓軸戲-秋鶴遷徙高峰期即將拉開序幕。經歷了這一切,我才心滿意足地離開了深秋的小鎮。

自海明森時代以來記錄的最大鶴潮發生在1990年11月10日:共有5種鶴,共有2728隻鶴、328只冠鶴、135隻丹頂鶴、6隻白頸鶴和111隻西伯利亞鶴,還有396隻身份不明。這是另一波沒有立即跟隨冷鋒的浪潮。

11 月 9 日,前線已經通過,我們三個人提前到達了蓮花山觀察點,希望有一個美好的一天。風勢強勁,為東北風,上午中旬變為西北風,下午中旬變為西風。天空晴朗,空氣寒冷——在沒有陽光照射的地方,花崗岩洞裡的冰整天都凍結著。猛禽是當天的明星:共有 13 個物種,其中包括 190 個高地猛禽 鵟 和四個粗腿 藍兔 禿鷹,六隻歐亞黑禿鷹 埃及斑蚊,三隻白尾鷹,以及大斑點鷹各一隻 天鷹, 草原 尼帕蘭 和帝國 赫利亞卡 老鷹。還有135隻東方白鸛和4隻黑鸛、14隻大鴇、10隻丹頂鶴和491只鶴,其中大部分是在下午晚些時候經過的,它們是浪潮的先行者。

第二天,天空再次晴朗,初風溫和,東北偏北。但風很快就變得微弱,在上午晚些時候轉向南風——不太樂觀。截至中午,登記的移民人數很少。

但是,在 28 隻白鶴向北飛後不久,一群 85 隻白鶴向南飛,標誌著通道的開始。

我們記錄了一系列小型、中型,偶爾還有大型雞群。從下午3點到4點,短短一小時內,就產生了四種鶴、1504隻鶴。大多數人正在向我們的東邊行駛,也許是越過大海,然後向西南方向移動。這似乎是秋季大群的典型特徵。一些較小的羊群經過我們的觀察點附近。

下午4點後,通道逐漸退潮,30分鐘內只有26隻起重機。但隨後,在日益陰暗的天氣中,海浪再次加速,更多的羊群飛越大海。他們變得更難看見,也幾乎無法辨認;只是在陰暗的灰色大海和天空的襯托下,一排排的黑點。下午5點15分,夜幕降臨,我們離開了哨所。

我們從山上步行下來大約花了20分鐘。當我們行走時,黑暗的天空中迴響著那些令人難以忘懷的、永恆的聲音;鶴的合唱,向南自鳴。

如果你有興趣去北戴河旅遊,可以聯絡鎮上天海旅行社的Jean Wang,該旅行社經常接待觀鳥團體/個人,可以安排去歡樂島等遊覽。 位元 [at] 0335.net 或 bsots [at] 263.net