Just measured as the crow flies, the main Ming Dynasty Great Wall stretches some 2000 kilometres from west to east. For much of its length, the Great Wall dips and climbs through mountain ranges, until at last dropping to a narrow coastal plain, crossing the town of Shanhaiguan – Pass Between Mountain and Sea – and ending at the shoreline.

Picture the crow now flying southwest from Shanhaiguan. The coastal plain widens, the mountains are lost from view, until after 30 kilometres there’s a place where outcrops of granite form low hills and headlands. Small bays cradle beaches, which helped make this place China’s most famous seaside resort – Beidaihe, or more strictly Beidaihe Haibin: Beidaihe-by-the-Sea.

These hills and headlands, plus woods and estuaries, also make Beidaihe a hotspot for migratory birds, which include crows, along with cranes, storks, eagles, thrushes and warblers, with several species that are rare worldwide. It was these birds that first drew me to the town, as leader of an expedition to study bird migration at Beidaihe forty years after observations by a Danish scientist, Axel Hemmingsen, and I have made at least 10 repeat visits, most recently in May 2019 [as I wrote this; followed by an autumn visit the same year].

That first expedition was in spring 1985, and China and Beidaihe were very different to today. Horses pulled cartloads of bricks and other materials through the streets, cars were scarce, and many people still aspired to own a bicycle, like the gearless Flying Pigeon brand cycles we used for exploring the town and nearby. But profound changes were underway, as with China’s reform process underway, Beidaihe was enjoying a resurgence as a resort for the masses.

Resort, hotspot for warlords, and summer locale for top government

While the unifier of China, Qin Shi Huangdi [221-210 BC], had a palace at Beidaihe, its origins as a resort date from around 1890, when British engineers working on a nearby railway line recognised its potential for seaside holidays, and let friends in nearby Tianjin know. Soon, westerners began arriving, some of them building houses and later vacation villas. In 1898, the Qing government formally declared Beidaihe a summer resort.

The China Daily has chronicled events at Beidaihe, describing it as “the first resort in Chinese history to allow local residents and expats to live in the same place”. Foreign diplomats and wealthy Chinese arrived. After the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Beidaihe became “a hotspot for the nation’s warlords”, and a summer resort for Kuomingang government officials.

Following the Communist Party’s rise to power, few foreigners holidayed at Beidaihe. The Great Helmsman, Mao Zedong, took a liking to the town, establishing a tradition of holding major government meetings at Beidaihe in summer. Later, Deng Xiaoping, paramount leader of China from 1978 until 1989, was likewise photographed swimming in the sea here.

Developed yet with small town character

Unsurprisingly given this storied history, we found Beidaihe was a curious town, with echoes of a genteel English seaside resort, along with a leadership compound where armed sentries stood guard. There were sanitoria for workers from coal mining and other industries along the south coast, and hotels with multiple buildings scattered amidst pine plantations.

In the years since, Beidaihe has developed in tandem with the transformation of China, whilst also retaining its small town character. The most dramatic transformations have been in nearby areas, particularly south of the town, where fields and sand dunes have given way to a brash new resort, Nandaihe, with hotels, restaurants and high rise apartment blocks.

No such high-rises yet mar the Beidaihe landscape, which still has hotel grounds amidst pine groves. Just as during that first bird survey, I enjoy cycling the narrow road along the south coast, passing hotels and small parks, beaches public and private, and rocky promontories where brides- and grooms-to-be pose for pre-wedding photos.

From the main public beach, a road leads up towards the town centre. It passes rows of buildings that seem loosely modelled on European style, with patterns on one recalling Britain’s Tudor architecture, another with three cheery looking figurines enticing Russian tourists – who now abound in Beidaihe during summer – to eat, drink, and be merry. McDonald’s has arrived, I notice, in a three storey building with windows akin to a Gothic church, topped by a dome and spire. It’s almost as if downtown Beidaihe has become a living theme park.

Nearby, I find remnants of old Beidaihe. There’s the Kiesling’s bakery, inside which is a photo of the establishment in the 1930s, when it was founded by Austrians, and called Kiesling and Bader’s. A sign points to “ancient villas”, and I cycle up a side road to bungalows with terraces such as Madame Avan’s Villa, built in the early 20th century (according to an information post beside it).

Birding at a reserve and a river mouth

Immediately north of the town, there are areas that birdwatchers including me helped spare from development, by highlighting Beidaihe’s importance for migrants. While that’s a rare win for conservation, these include what may be the world’s weirdest wetland reserve.

This has a grandiose Qinhuangdao Bird Museum – under renovation in May, but featuring exhibits such as a model pterosaur when I first went, in 2009. Trees planted beside it have reduced the wetland area and obscured the view. There’s a fence around a small estuary, and with wild birds now distant, trees are hung with fake plastic nests, and the main “bird calls” are recordings broadcast through loudspeakers on surveillance camera posts.

Happily, local birdwatchers introduce me to a far better, newly established reserve at the mouth of Stone River beside Shanhaiguan. Lagoons host shorebirds, spoonbills, herons and ducks, while migrant songbirds like cuckoos and vibrant Siberian blue robins frequent the woods.

Great Wall on plain and hills

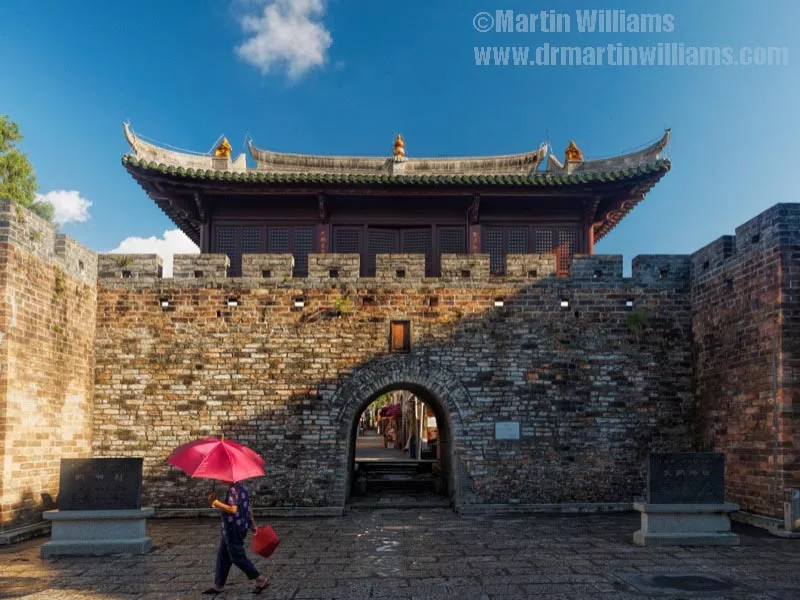

This reserve is just a couple of kilometres south of Old Dragon’s Head, where the Great Wall reaches the sea. I’ve been before, and thought the name more exciting than the place, which had little but rebuilt wall like a stone pier. So this time, I skip it, along with the “ancient city” that still features a gate in the wall known as “The First Pass Under Heaven”, but where old buildings were demolished and rebuilt in the last couple of decades, creating an ancient city that’s mostly brand new.

Instead, I head to the Jiao Shan, where the coastal plain ends, and the Great Wall leads up the slopes of Jiao Shan, Corner Hill. This too has been rebuilt – in 1985, I climbed the original wall here, finding it weathered, in places crumbling, but with battlements that had defied the elements for over three centuries.

Though this is a tourist site, the Great Wall retains its grandeur and allure. Usually, there’s a chairlift operating (closed for repairs in May), but climbing the wall itself is more rewarding. The steps are uneven, sometimes knee height or above, and there’s an optional metal staircase around a squat, square defensive tower I readily take, rather than clamber up a ladder as before.

The wall is little more than a nominal strip of brick and stone across the craggy 519-metre summit, fading away altogether on near vertical rock faces. There are more hills to the west, but no views of the wall rolling and climbing, receding into the distance.

After a pleasant walk up a path through trees, there’s a renovated temple with no monks in sight, and a vantage over a reservoir below. Eastwards and southwards lie the coastal plain, with haze typically obscuring the nearby sea, and the low hills of Beidaihe, east China’s off-the-wall magnet for people and birds alike.

If you go

There are buses from Terminal 3 of Beijing Airport to the city of Qinhuangdao, between Shanhaiguan and Beidaihe. The journey takes around four hours, and you could then take a taxi to Beidaihe.