Written 23 January 2020; I’ve added a few later remarks in square brackets.

With pandemic diseases sometimes causing huge death tolls – notably bubonic plague killing an estimated 50 million people in Europe alone during the 14th century, and Spanish Flu infecting maybe 500 million people worldwide, with 20 to 50 million of them dying, from 1918-1920 – the emergence of a new disease can quickly grab attention. Especially now, given the sudden emergence of a coronavirus [later called Covid-19] that [likely… or just maybe, I later believe] originated among exotic animals sold for food in mainland China, with strong similarities to the SARS outbreak that killed 299 of the 1,755 people infected in Hong Kong during 2013.

Perhaps it’s all too easy to get caught up with notions of imminent doom, like a real-life disaster Hollywood disaster movie. I’ve done so before, becoming fascinated by dire online predictions of SARS, and even influenza researcher Robert Webster claiming bird flu could kill up to half the human population. But science reveals such fears are groundless, while also indicating actions that individuals and governments can take to reduce disease spread, and the potential for pandemics.

Though it may not seem obvious the coronavirus can’t become increasingly lethal, given the mutations and mixing possible with its genetic makeup, the natural brake on its virulence arises from Darwinian principles. Such principles may seem readily overlooked by virologists such as Robert Webster, yet have been successfully applied to disease by evolutionary biologist Paul Ewald, director of the program in Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Louisville, US.

Ewald’s insights originated with a bout of diarrhoea, during which he wondered why the illness symptoms included expelling huge amounts of the pathogenic bacteria. But instead of being wasteful, he realised this mechanism could help the diarrhoea spread, and he began looking at the relationship between evolution and the virulence of diseases.

Influenza – flu – interested Ewald, partly as it can change quickly, and while most strains are relatively benign it can become more virulent, with a higher fatality rate. Ewald realised that flu strongly relies on being transmitted between people, so infected people had to move around in order for it to be spread, which in turn meant typically influenza must be mild. But looking at Spanish Flu, Ewald decided its timing did not just happen to coincide with the First World War (1910–1917). Instead, it was a product of that war, especially the trench warfare.

While people struck down by intense flu are normally bedridden, interacting with few people at home or in hospital, soldiers with flu might have been in trenches and field hospitals near tens or hundreds of people. In these conditions, the flu virus evolved to a more potent form. Even as it began spreading, wartime censors downplayed reports of its severity; the name derives from uncensored news reports in Spain, which was neutral during the war.

Though not all disease experts agree with Ewald, his theories regarding diseases and evolution have at times been put to the test, and proven successful. “Paul Ewald is a short-seller of global pandemics. He bets against them when panic reaches its peak,” according to an article in Esquire – which noted he, “short-sold SARS and bet against bird flu, and in both cases he was famously right.” That article appeared in 2014, when there were concerns of a deadly Ebola pandemic. Ewald forecast that highly lethal Ebola would be contained, or would have to someday become a mild disease, to survive in humans.

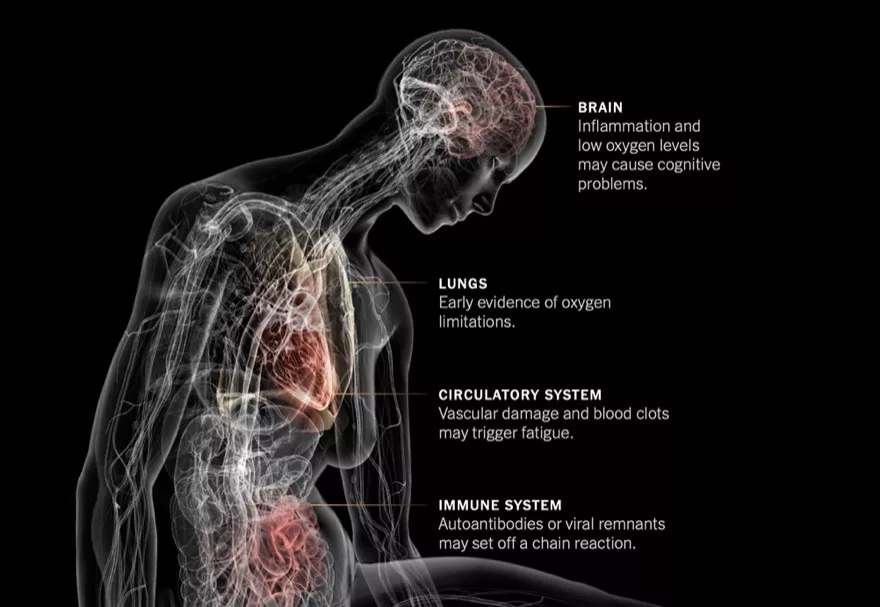

With no word from Ewald regarding the Wuhan coronavirus (I’ve emailed him, but no reply as yet), perhaps it’s worth guessing what evolutionary biology might tell us. It’s early days yet, with relatively little information, but indications are that it’s less virulent than SARS: Professor Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London has told Yahoo News the death rate could be 2%, which is similar to Spanish Flu. Just maybe, this means it can be readily transmitted by mobile people, and indeed cause a pandemic. Of course, only time will tell; updates will soon reveal more.

At an individual level, there’s a focus on face masks, as during SARS. Yet it’s questionable that they are really useful, with a review of research into face masks and flu concluding, “There is little evidence to support the effectiveness of face masks to reduce the risk of infection.” I even wonder if they can give a false sense of security, especially the paper masks that readily let in small particles. [Soon after writing this, I was persuaded of the value of face masks by Professor Yuen Kwok-yung, who kindly emailed me information that set me right re my doubting message to him.]

Other research on viruses including flu and colds has found that while droplets carrying them stay airborne for up to 10 minutes after an infected person sneezes, they can then stick to surfaces and remain infectious for hours, or even a day or more on hard surfaces. So the advice on washing hands, maybe using hand sanitizers, is highly important; likewise resisting the temptation to scratch or rub at itchy eyes and nose. [For Covid, seems the main transmission route – by far – is airborne, even travelling some distance in aerosol form; consider a bit like the way exhaled cigarette smoke can travel.]

To me, the importance of the latter was highlighted back in 2003, when I interviewed Dr Yannie Soo, who courageously worked in a ward with SARS patients. She told me of a medic who was in the ward and scratched quickly beneath his mask, which evidently led to him becoming infected with SARS.

As to governments, various actions are possible. Screening of travellers might seem important, yet in researching this article I found it is of limited value, which explains how some cases have slipped through the net. Quarantining the entire city of Wuhan is an astonishing measure, especially occurring after the Wuhan coronavirus has travelled as far as the US.

Looking ahead, China’s most vital action should aim to counter the emergence of similar diseases. Reports link the Wuhan coronaviris with a seafood market that includes stores selling “exotic” animals; so like various other live food markets in China, it could be like a mixing pot for diseases. SARS evidently started with a bat disease, which infected, spread and evolved in civets before reaching humans; early research suggests the Wuhan coronavirus is similar, but reached humans via snakes. [Now, I believe Covid was from a lab, after tweaking of coronavirus that would otherwise have remained mostly restricted to bats, not readily infecting humans.]

While such markets persist, the likelihood of other new diseases appearing will remain. Surly it’s time for China to clamp down, and close them down; which will also benefit progress towards nature conservation and animal rights, as well as reducing the risk a made in China disease could harm people worldwide.